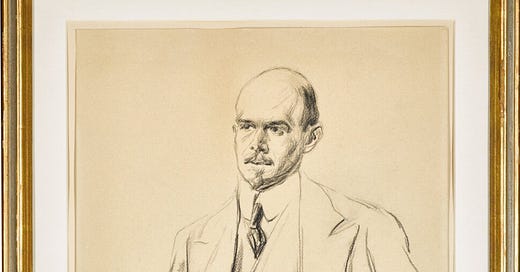

Max Liebermann (1847-1935), Berlin, Portrait of Walther Rathenau. Black chalk and blue crayon/chalk; signed in black chalk, lower right: M.Liebermann, and also bears faint signature (rubbed out) lower left. From a Sotheby’s catalogue available online.

Also from Sotheby’s:

Conveniently, the dating of this elegant portrait of the German industrialist, writer and politician Walther Rathenau (1867-1922) can be deduced with some precision from his diaries, where we read, under 26 October 1912: ‘Jeden Mittag beim Zahnarzt. Dazwischen von Max Liebermann gezeichnet, für Hauptmann’ (‘Every lunchtime to the dentist. In between, drawn by Max Liebermann, for Hauptmann’). The drawing was made to be given as a present to the prominent writer Gerhart Hauptmann (1862-1946) on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday, on 15 November 1912. In this same year, Hauptmann won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Shortly after the lavish birthday festivities, Hauptmann wrote to Rathenau, thanking him warmly for his extremely thoughtful gift.

Walther Rathenau was the son of the Jewish founder of the German electrical engineering firm, AEG, and assumed the chairmanship of the company in 1915, following his father’s death. Throughout the First World War, Rathenau played an important role in organising the German war economy, and having formed a new political party, the German Democratic Party, was politically prominent in the post-war Weimar Republic, holding the positions of Minister of Reconstruction and Foreign Minister. In this latter capacity, Rathenau negotiated the 1922 Treaty of Rapallo, which normalised relations and strengthened economic ties between Germany and Soviet Russia. Rathenau also insisted that Germany fulfil its obligations under the Treaty of Versailles, and soon came to be branded by right-wing nationalist groups (including the emerging Nazi Party) as part of a Jewish-Communist conspiracy.

Just two months after the signing of the Treaty of Rapallo, members of an ultra-nationalist paramilitary group called Organisation Consul assassinated Rathenau as he drove to work along Berlin’s Königsallee.

Dear Subscribers,

After a slow, deliberate, and deliberately plodding start, The Man Without Qualties is starting to come together with our reading for this coming week. And the character of Arnheim, arguably, is the binding element.

In case you need a reminder about our upcoming reading targets, here they are:

Week 3 (ends Monday, October 21): chapters 32 through 45.

Week 4 (ends Monday, October 28): chapters 46 through 62.

Week 5 (ends Monday, November 4): chapters 63 through 76.

Tuesday, November 5 is election day in the U.S., so we’ll either be going the way of Kakania and drifting into our own extinction as a country when the results are finally in and certified, or we’ll be hanging on by our fingernails to remain a viable country. I am not in the prediction business, but I am a believer in the optative mood, in writing and in politics, so that is where I’ll dwell.

A request: I know from Substack’s analytics, which are a little scary, to be honest, that a vast majority of you, more than 80%, are opening and reading these posts on TMWQ when they go out every week. That’s great. I hope you’re finding them to be helpful as you embark on this 10-week project in close, deep and dynamic reading. I’d like to try and get that same 80%—or as close to the number as we can reach—to begin posting in the comments threads as well. Send your questions about the book, your thoughts about the characters as they come into better focus, your struggles (if you are having them) with Musil’s method and his ambitions for the novel. I’d also like to know if there are different kinds of background I can be providing—Susan’s thinking about the character Arnheim in a follow-up to one of last week’s posts has led directly to this week’s post about Kakania, Walther Rathenau (the real-life model for Paul Arnheim), and character construction in the novel.

I have opened up the comments section to all subscribers (not just paid subscribers) to encourage more engagement and to hear what you have to say about your reading …

A whiteboard diagram of the character relations in TMWQ as a series of overlapping triangles

As I mentioned in the comments section of the last post, “The Beethoven Frieze,” I’ve become quite enamored of building a diagram of character relations in TMWQ when I teach the novel in the classroom, both to help “tame” the novel is it begins to sprawl its way ever outward and to illustrate (hopefully) the logic of its network of relations—as Susan has already suggested, TMWQ is a “systems” novel first and foremost, with the prevailing organizing principle being the rigidly hierarchical structure of Austria under the Dual Monarchy of the Hapsburgs.

There is probably an even more precise way to build a diagram of the characters and their network of relationships in the novel, one that takes into account the layers of the society and its administration:

The Aristocracy

Diplomacy // the Military // the Civil Service

the Bourgeoisie (non-Jewish and Jewish) // the Arts

the Servant class // the Criminal class

The novel’s large cast of characters divides pretty neatly among these categories. A few examples: Count Leinsdorf (aristocracy), General Stumm von Bordwehr (military), Section Chief Tuzzi (diplomacy), Diotima and Ulrich (the bourgeoisie), Rachel and Soliman (the servant class), Moosbrugger (criminal class).

The Parallel Campaign, doomed to fail though it is, has brought together all of these actors in society for a single purpose, with Diotima as their presiding deity—this is just one of the novel’s internal jokes/ironies, Diotima of Plato’s Symposium being a high-priestess who indoctrinates Socrates into the mysteries of love/eros, while Frau Tuzzi is altogether more Austrian and earthbound.

If you look at the individual triangles of relations here, you’ll see different kinds: there is Ulrich —> Diotima —> Arnheim, for example, which begins as a traditional "love” triangle, however ironized, with Diotima at the center and the two men drawn to her by attraction. The novel’s opening suggests that Diotima and Arnheim are involved in an affair, complete with secret meetings in Vienna when Tuzzi is away, and this hangs over the depiction of their relationship for the remainder of the novel. Ulrich has eyes only for Diotima early in the novel, but then Arnheim exerts the stronger gravitational pull—one so powerful, in fact, that Ulrich is tempted to give up his urlaub vom leben early to go and work for the great man as a private secretary.

There is Ulrich —> Clarisse —> Walter, a simmering triangle of a familiar romantic variety; Leo Fischel —> Gerda Fischel —> Ulrich, a volatile though also rather hapless attraction between Ulrich and the younger (Jewish) Gerda, overseen by her father; and Soliman’s turbulent pursuit of Rachel, which is triangulated by the magnetic presence of Arnheim, and doubled by the triangle between Diotima —> Arnheim —> Rachel.

Just as everyone in the service of Emperor Franz Joseph I had a role in the Austria of the Hapsburgs, and their identity—their character—was indivisible from this public identity, often denoted by a specific uniform or feather in a cap or medals on a jacket, the characters in the novel are shells of a character first, with their insides, their private substance, open for speculation. And the novel’s essayistic method is perfectly attuned to this—the narration/narrator cycling through different theories and speculations about what may or may not be happening in any given character’s interior rather than providing the illusion of unmediated access.

We didn’t read the chapters for this week, but I’d like you to pay particular attention to two chapters concerning Arnheim for next week’s reading: 47, “What All Others Are Separately, Arnheim is Rolled into One,” and 48, “The Three Causes of Arnheim’s Fame and the Mystery of the Whole.”

These twin chapters have a lot to tell us about Arnheim as a constructed whole in the novel, but also about Musil’s notion of what characters in fiction are in the first place, which is quite singular in all of literature, I would argue.

As Ulrich reflects on Arnheim’s magnetism in ch. 47:

“That’s no longer intellect,” Ulrich said, explaining the general amazement, “it is a phenomenon like a rainbow with a foot you can take hold of and actually feel. He talks about love and economics, chemistry and trips in kayaks; he is a scholar, a landowner, and a stockbroker; in short, what the rest of us are separately, he is rolled into one; of course we’re amazed.”

A rainbow with a foot you can take hold of and actually feel. What a strange, beguiling idea.

I hope to hear from you, and until soon—

Bis bald.