The Little General in the Forget-me-not Blue Uniform

How one indelible character can restore the focus of a novel threatening to sprawl out of its author's control--and leave the reader out in the cold

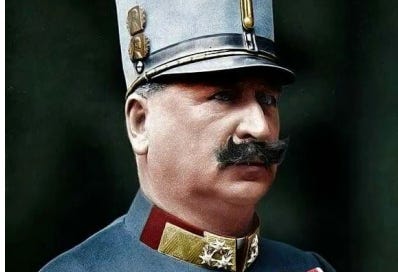

A photographic portrait of Austrian field commander Franz Freiherr Rohr von Denta (1854-1927), an Austro-Hungarian Field Marshal who served as the last commander of the Austro-Hungarian First Army. Note the forget-me-not blue uniform and imperial mustache.

General Franz Freiherr Rohr von Denta on horseback, posed in front of a snow bank. There are echoes of General Stumm von Bordwehr in the General’s paunch and the awkwardness of his posture on horseback. Image from https://wargamescratch.wordpress.com

Dear Subscribers,

If I had the chance to initiate this Substack all over again, I think I probably wouldn’t start with a 10-week reading course on Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities—instead, I would build up to this project over time and kick things off by creating a Feuilleton page for the internet first, a newspaper section of sorts for fun, insightful, literate, and generally unclassifiable pieces of writing by the writers I read, follow and admire. So, I would be an editor first and a writer second. Not unlike Robert Musil’s brief stint as an editor at the journal Die Neue Rundschau (“The New Review”), which brought Musil into contact with a visionary contemporary of his from Austria’s outer reaches in Bohemia, Franz Kafka. (Musil was born in 1880, Kafka in 1883.)

In fact, Musil was ready to publish Kafka’s long story “Die Verwandlung” (most often translated as “The Metamorphosis”) in the Rundschau, but the journal’s head editor, Samuel Fischer, in one of those decisions that can haunt a publisher for a lifetime, insisted on changes to the story that Kafka refused to make.

One of the reasons I am continually drawn to Robert Musil and the early Modernist period in European literature is the sense of an openness to experimentation that is absolute; comfort with a fiction rooted in ideas; and the audacity to write alternate histories—especially when the history you are living, as Stephen Dedalus famously reflects in James Joyce’s Ulysses, “is the nightmare from which I am trying to awake.”

This brings us to the subject of today’s post, and possibly my favorite character in the novel as a whole, General Stumm von Bordwehr—an uninvited guest to the meetings of the Parallel Campaign, dressed in the forget-me-not blue of the Austrian military, who stealthily works his way into the uppermost precincts of the campaign and then captivates Ulrich with his jaunty credulousness, the “little toothbrush on his upper lip in place of a real mustache,” and the comic impossibility of picturing this “pudgy little man” on horseback (see the second photo above).

General Stumm makes his first appearance in the novel in ch. 42, “The Great Session.” In one of the novel’s more virtuosic moves, Stumm appears not as a character first, but as a “golden sword knot” spied through a keyhole by Diotima’s Jewish maid Rachel:

She fluttered to the door, which she opened unceremoniously, and the crouched down at the keyhole to see what would now happen inside. It was a large keyhole, and she saw the banker’s clean-shaven chin and the prelate Niedomansky’s violet neckband, as well as the golden sword knot of General Stumm von Bordwehr, who had been sent by the War Ministry although it really had not been invited; the Ministry had declared, in a letter to Count Leinsdorf, that it did not wish to be absent on “so highly patriotic” an occasion, though not directly involved in bringing it about or in the foreseeable course it would take.

First, this passage is a breathtaking example of the narration’s fluidity and precision, of how it cycles through intervals in the distant 3rd person of an observing narrator (“fluttered to the door,” “opened unceremoniously,” “It was a large keyhole”) before employing Rachel’s interior as a descriptive tool (“she saw the banker’s clean-shaven chin and the prelate Niedomansky’s violet neckband …”) for a moment and swiveling to a parody of official communications in Kakania—the pompousness and illogic of the Imperial voice (“the Ministry had declared, in a letter to Count Leinsdorf, that it did not wish to be absent on ‘so highly patriotic’ an occasion, though not directly involved in bringing it about or in the foreseeable course it would take …”).

Stumm next appears in ch. 44, “Continuation and Conclusion of the Great Session …” The reader will already know Stumm is an uninvited guest, acting on orders, though Diotima and even Count Leinsdorf are in the dark about why the stubby little uncouth General has joined their hallowed company.

Someone asked as a point of further clarification how the specifically Austrian note could come into the campaign as thus conceived.

This is when General Stumm von Bordwehr rises to speak to the illustrious group, “even though all of the preceding speakers had remained seated.” (I winced a bit for General Stumm here, feeling a twinge of sympathy for how out of place a soldier and his sense of duty are among the gathered elite.) He is overawed by his audience, stiff in his demeanor and without anything of importance to share—his speech comes out in a jumbled gloss. Here is the preamble:

He was well aware, he said, that soldier’s role in the council chamber was a modest one. If he spoke nevertheless, it was not to inject his own opinion into the unsurpassable critical remarks and suggestions already made, all of them excellent, but only to offer one more idea at the end, for everyone’s indulgent consideration.

Writing convincingly about dullness and boredom is one of the most difficult things to do in fiction. David Foster Wallace takes the fully immersive route in his collection Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, and elsewhere, creating states of readerly boredom, even stupefaction, that are “both funny and intolerable,” as the critic James Wood has written. (For a quick reminder about the whole Wood/Wallace contretemps, there is this video of Wood tying himself in knots about Wallace’s work, quite graciously, at the 92nd Street Y in 2010.)

Musil’s approach to representing the tediousness of the official proceedings of Count Leinsdorf’s great Campaign is to establish the stupefaction first in a relatively quick glimpse, then to zoom out and show a more dynamic minor character observing at a keyhole or through a crack in the door—such on page 192, when Rachel, Diotima’s maid, suddenly issues a report on the proceedings to an unnamed audience.

At the keyhole, “Rachelle” reported: “Now they’re talking about war.”

Rachel is spying through the keyhole with Arnheim’s manservant Soliman, who represents one more complication—one more bond—in the novel’s network of relations (see the bottom right of this diagram).

Soliman —> Arnheim —> Rachel form one dynamic triangle. Rachel —> Diotima —> Arnheim form another. They tug against one another at their points of intersection.

Rachel’s allegiance to Diotima is continually tested when she consorts with Soliman and risks exposure. Ulrich —> Rachel —> Diotima form another dramatic triangle in the novel’s rational design, with Rachel exerting a strong, separate gravitational pull for both Ulrich and and Diotima—who, let’s not forget, are cousins.

Stumm’s real marvel of a chapter, though, his “Racehorse of Genius” moment, comes a little further on in our reading, at the end of last week’s pages: ch. 85, “General Stumm Tries to Bring Some Order into the Civilian Mind.” Ulrich has just left the order of his house to spend a chapter in the company of two very disordered civilian minds, Walter and Clarisse.

Walter could not make himself look at her. Her capacity for refusal was, after all, a major factor in their life together; Clarisse, looking like a little angel in a long nightgown that covered her feet, had stood on her bed declaiming Nietzschean sentiments, with her teeth flashing, “I toss my question like a plum line into your soul! You want a child and marriage, but I ask you: Are you the man to have a child? Are you the victorious master of his own powers? Or is it merely the voice of the animal in you, the slave of nature, speaking?

Are you the victorious master of his own powers? If this is how people spoke in the series Couples Counseling, I might actually watch …

In any case, Ulrich has just returned home from a visit to this desperate spectacle and he is told that a “military gentleman” is waiting for him.

“Do forgive me, old friend,” the General called out to him in welcome, “for barging in on you so late, but I couldn’t get off duty and sooner, so I’ve been sitting here for a good two hours, surrounded by your books—what terrifying heaps of them you’ve got!”

Stumm has come to Ulrich for some assistance with an “urgent problem.” And it is a problem of his own making, given that Stumm has been surveying the invited guests at the meetings of the Parallel Campaign about their “main ideas” for the theme of the Austrian Year to celebrate Emperor Franz Joseph’s reign Duotima has convened them all together to brainstorm.

“They can say what they like about us,” [Stumm] said, “but we army men have always known how to get things in order …”

Stumm’s first problem with his survey of the illustrious guests is that “every one of them, when you ask him privately, places a top priority on something different.” He has tried to record his survey data in an orderly fashion, creating something like an Excel Spreadsheet by hand, but the resulting document is absurdly complicated.

Ulrich looked at the paper in astonishment. It was drawn up like a registration form or, in fact, a military list, divided by horizontal and vertical lines into sections, with entries in words that resisted the format, for what he read here, written in military calligraphy, were the names of Jesus Christ; Buddha, Gautama, aka Siddhartha; Lao-Tzu; Luther, Martin; Goethe, Wolfgang; Ganghofer, Ludwig; Chamberlain, and evidently many more, running on to another page. In a second column he read the words “Christianity,” “Imperialism,” “Century of Interchange,” and so on.

This is almost Stumm’s crowning moment in the novel, the apex of his comic role in exposing the disunities between the instruments of Imperial power, the fading order of a sprawling empire, and the destabilizing effects of what Adorno and Horkheimer called the “ruthless unity” of market forces in both culture and politics.

I say ‘almost,’ because Stumm’s last great walk-on in the novel comes at the end of our reading for the current week, ch. 100, “General Stumm invades the State Library and learns about the world of books, the librarians guarding it, and intellectual order.”

This is all very funny, and Stumm provides a much needed respite from the loftiness of Ulrich’s perpetual musings on … everything. But there is a more serious purpose to Stumm’s role in the book—and his befuddlement by the ways of civilians. In Marjorie Perloff’s chapter on Musil in her book Edge of Irony: Modernism in the Shadow of the Habsburg Empire, she includes a series of entries that Musil recorded in a notebook that he kept after the Anschluss in 1938, when he and his wife were living in exile:

Overall problem: war.

Pseudorealities lead to war. The Parallel Campaign leads to war!

War as: How a great event comes about.

All lines lead to the war. Everyone welcomes it in his fashion.

Sobering thoughts for our own national slide into pseudoreality.

Here is one more reminder of our reading targets:

Week 7 (ends Monday, November 18): chapters 87 through 100.

Week 8 (ends Monday, November 25): chapters 101 through 110.

Week 9 (ends Monday, December 2nd): chapters 111 through 116.

Week 10 (ends Monday, December 9): chapters 117 through 123.

Bis Bald,

B.A.