Sabbatical from Life

Why launch a new literary Substack now?

There’s a phrase in German I’ve been obsessing about ever since I taught Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities a few years ago: “urlaub vom leben.” The literal translation of urlaub vom leben is “vacation from life,” though there is more than a little irony in Musil’s use of urlaub/vacation—as there is in many of the precise language choices in his long, unfinished masterwork—given the strenuous nature of Ulrich’s self-imposed period of idleness that brackets the first part of the novel.

Ulrich is the protagonist of The Man Without Qualities, for those who haven’t made a heroic attempt at tackling the 1,800 pages or so of the Sophie Wilkins and Burton Pike translation yet. For my money, sticking to the relatively compact 752 pp. of the first volume, encompassing the first two original installments, re-titled, in translation, A Sort of Introduction and Pseudoreality Prevails, is the best way to begin an immersion into Musil’s digressive brilliance.

And the first volume of the Wilkins/Pike The Man Without Qualities is the perfect length to read carefully, slowly, over ten weeks—75 pp. of Musil’s heady, confected, philosophically dense prose, the literary equivalent of Cremeschnitte, is the most you can expect to read attentively in a week.

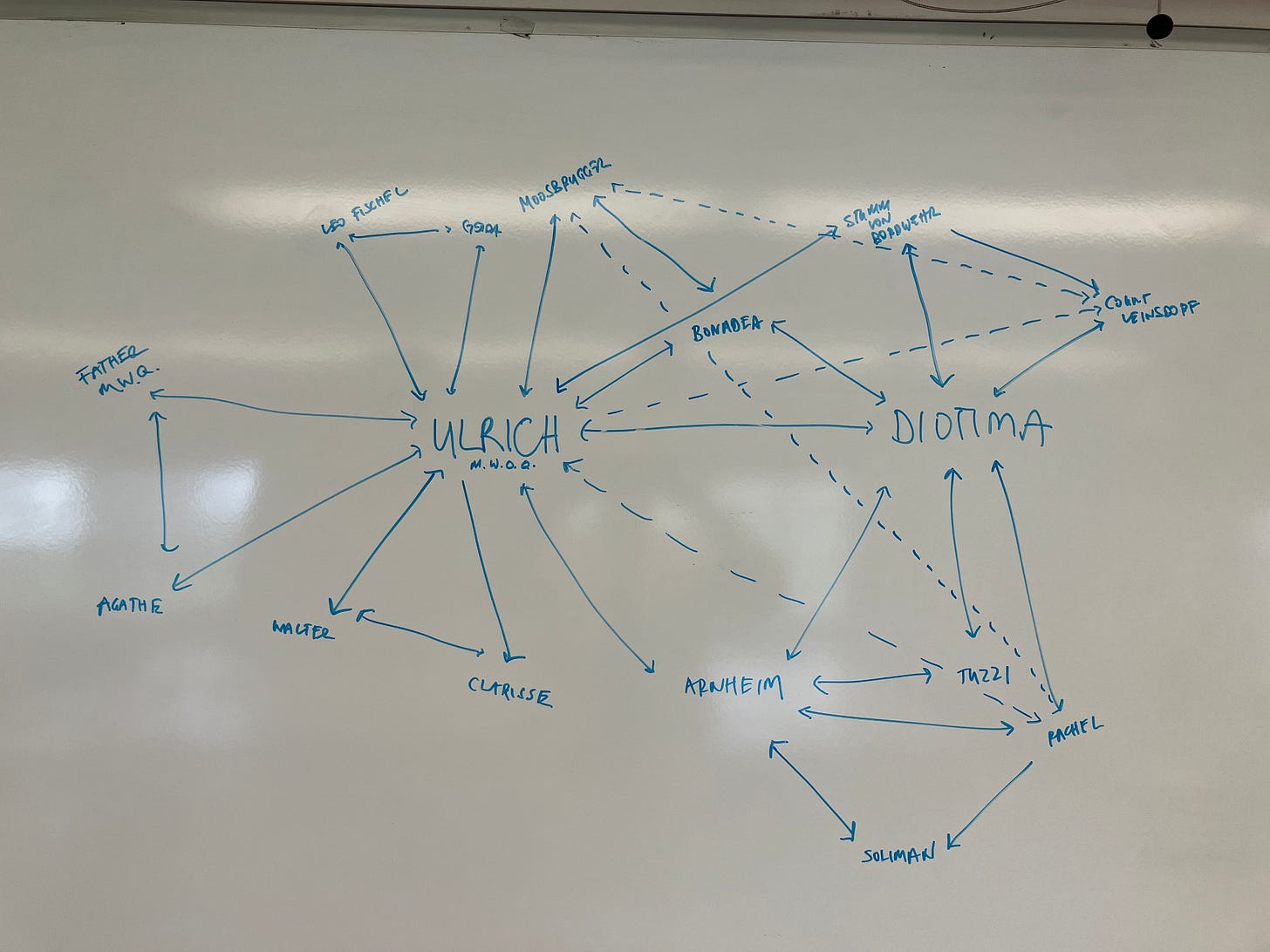

Even in the most gripping sections of the novel, like the closing pages of Pseudoreality Prevails, when the structure of competing dramatic triangles pulls the action almost impossibly taut (see the diagram I drew on a whiteboard at Bennington below), the characters speak in abstractions so billowingly light they sometimes unmoor the reader from the world of the characters and the historical present they inhabit.

A schematic diagram of the novel’s dramatic structure: a series of interlocking triangles, with Ulrich and his cousin “Diotima” as the centers of gravity.

It’s a novel that scrapes the bottom of the sky over 1913 Vienna and keeps threatening to lift off into the realm of the Platonic ideal.

Everything partakes of the universal and also has something special all its own. Everything is both true to type and refuses to conform to type and is in a category all its own, simultaneously. The personal quality of any given creature is precisely that which doesn’t coincide with anything else. I once said to you that the more truth we discover, the less of the personal is left in the world, because of the longtime war against individuality that individuality is losing. By the time everything has been rationalized, there’s no telling how much of us will be left. Nothing at all, possibly, but then, when the false significance we attach to personality has gone, we may enter upon a new kind of significance as if embarking on a splendid adventure (624).

[This is Ulrich, of course—in a soliloquy addressed to his cousin Diotima.]

The truth is, Musil is often overmatched by the self-imposed demands of his own creation. The fluency of passages like the one above is a central malady of the novel as much as it is a sign of its brilliance and essential health. There is too much thinking in The Man Without Qualities, too much contingency and possibility, too much waffling and indecision in Ulrich’s progress through its pages. (The novel diagnoses this condition as “living hypothetically.”) Still. There is a precision of language, and a revelation of thought, that is unmatched in any other work of fiction I know of. Such as:

From Chapter 11, “The Most Important Attempt of All”:

It is the fulfillment of man’s primordial dreams to be able to fly, travel with the fish, drill our way beneath the bodies of towering mountains, send messages with Godlike speed, see the invisible and hear the distant speak, hear the voices of the dead, be miraculously cured while asleep, see with our own eyes how we will look twenty years after our death, learn in flickering nights thousands of things above and below this earth no one ever knew before …

From Chapter 62, “The Earth Too, But Especially Ulrich, Pays Homage to the Utopia of Essayism”:

If someone had asked [Ulrich] at any point while he was writing treatises on mathematical problems or mathematical logic, or engaged in some scientific project, what it was he hoped to achieve, he would have answered that there was only one question worth thinking about, the question of the right way to live.

From Chapter 87, “Moosbrugger* Dances”:

He spat and thought of the sky, which looks like a mousetrap covered in blue. “The kind they make in Slovakia, those round, high mousetraps,” he thought.

(*Moosbrugger is a sex-murderer whose case shadows the primary plot of the novel.)

The bubble of authors’ Substacks has already burst. Or maybe there was never really a bubble in a market sense: just an open, unpopulated field for writers and readers that was quickly glutted with literary Substacks and has been for some time now. I know that I’ve been cutting back on subscriptions lately to save both time and money. So why join the Substack Steeplechase for paying subscribers now, at this late hour?

(1) Like Ulrich in The Man Without Qualities, I am taking an “urlaub vom leben” for the next sixteen weeks. I am on sabbatical from Bennington and will be working on a novel, along with some other new writing projects I’ve been planning and am excited about. If you’re interested in hearing more about these projects as they develop, just subscribe.

(2) It’s time for me to read The Man Without Qualities again. And I hope you’ll be interested in reading the first volume of the Wilkins/Pike translation along with me. Beginning in October, I’ll be posting regular essays about Musil and the novel for subscribers, with useful background and critical commentary. Subscribers to the series can communicate both on and off the site, post questions and reading notes, be a part of a community as we embark on a very singular reading experience. I have run small, intimate classes on Musil’s novel like this before, and I look forward to updating the support material with new insights and updated scholarship.

(3) This guided reading class will run for ten weeks (October 1-December 10) and give you access to both the course materials I post and to anything else I decide to write on the Substack: previews of new work, lost fragments of older work, commentary on the issues of the day.

I hope you’ll want to sign up. New material will begin appearing over the next 10 days / two weeks.

Who knows: maybe you’ll start to see a world of useful parallels between our own teetering Republic in 2024 and Musil’s threadbare empire of Kakania in 1913?

You can reach me at Benjamin.anastas@gmail.com with any questions.

Bis bald.

B.A.

Great, Ben. I'm in. I've always wanted to open that book and now you've given me reason, and hopefully, guidance! I'm reading Zweig's The World of Yesteryear and hear resonances in your depiction of Musil.